WORDS OH YAN TING, DR MUNIRAH ISMAIL & PROFESSOR DATO’ DR ROSLEE RAJIKAN

FEATURED EXPERTS

OH YAN TING OH YAN TINGDietitian and Student of MHSc in Clinical Nutrition Faculty of Health Sciences Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia |

DR MUNIRAH ISMAIL (PhD) DR MUNIRAH ISMAIL (PhD)Lecturer and Dietitian Dietetics Program Centre for Healthy Ageing and Wellness (H-CARE) Faculty of Health Sciences Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia |

PROFESSOR DATO’ DR ROSLEE RAJIKAN PROFESSOR DATO’ DR ROSLEE RAJIKANProfessor in Clinical Nutrition and Dietetics Centre for Healthy Ageing and Wellness (H-CARE) Faculty of Health Sciences Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia |

Parkinson’s disease is a degenerative neurological disorder affecting movement.

It occurs when there is damage to brain cells that results in a reduction of dopamine, a chemical in the brain that controls movement, mood, concentration, and others. A lack of dopamine will result in the brain’s nerves being unable to effectively regulate the activities as mentioned earlier.

Individuals with Parkinson’s disease usually experience motor symptoms such as tremors, slower body movements, limb stiffness, postural instability, and uncoordinated body movements. In addition, they may also suffer from depression, behavioural changes, sleep disorders, constipation as well as smell disorders.

PARKINSON’S DISEASE IN MALAYSIA

To date, approximately 15,000 to 20,000 Malaysians have been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, and this number is expected to increase by five times in the year 2040.

CAUSES & CURE

Various factors can contribute to the development of this disease, including genetic predisposition and environmental factors such as diet and physical activity as well as exposure to toxic agents such as heavy metals and pesticides.

Although the cause of Parkinson’s disease is not fully understood, there is evidence to suggest a link between oxidative damage, chronic neuroinflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction, which can result in the development of this disease.

Currently, there isn’t a cure for Parkinson’s disease. Therefore, preventive measures must be implemented to reduce one’s risk of developing this disease.

NUTRITION & PARKINSON’S DISEASE

Nutrition is one of the environmental factors found to influence one’s risk of developing Parkinson’s disease.

A high intake of vegetables as well as fish and legumes are moderately associated to a reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease.

Meanwhile, high consumption of meat, processed meat, sugary foods, and carbonated drinks is associated to an increased risk.

THE MEDITERRANEAN DIET

The Mediterranean diet is practiced widely in Greece, Spain, and Italy.

Many previous studies found that this diet confers benefits for health and longevity.

It is associated with a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke.

In addition, the Mediterranean diet is also widely recognized for its role in reducing oxidation and inflammation in the body. Since the onset and progression of Parkinson’s disease involve neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, the Mediterranean diet can therefore play an important role in the prevention of this disease.

Two large cohort studies have shown that a high level of adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with a lower risk of Parkinson’s disease. Whereas a lower level of adherence to this diet is associated with an earlier onset of Parkinson’s disease.

In addition, short-term adherence to the Mediterranean diet has also been found to reduce constipation, which is one of the signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

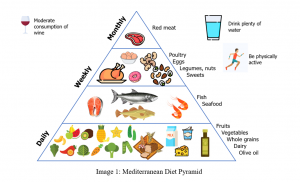

Characteristics of the Mediterranean diet.

This diet emphasizes the following 4 components:

High intake of fresh fruits and vegetables, as well as whole grains. According to the Greek Dietary Guidelines 1999, it recommends the following:

- Vegetables: 6 servings a day.

- Fruits: 3 servings a day.

- Whole grains: 8 servings a day.

These foods contain high dietary fibre, vitamins, and polyphenols. Vitamins A, C, and E and polyphenols contain antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that are likely to reduce the risk of Parkinson’s disease. In addition, the high dietary fibre content can also help to reduce occurrences of constipation.

Consistent use of olive oil. This oil contains monounsaturated fatty acids and polyphenols that can reduce oxidative stress and inflammation.

Consumption of milk, dairy products, potatoes, chicken eggs, fish, nuts, legumes, seeds and red wine in moderation.

- Milk and dairy products: 2 servings a day.

- Nuts and legumes: 3 to 4 servings a week.

- Fish or seafood: 5 to 6 servings a week.

- Chicken or duck: 4 servings a week.

- Eggs: 3 servings a week.

- Red wine: no more than 2 glasses a day for men and 1 glass a day for women.

Foods such as nuts, legumes, fish, chicken, and eggs are important sources of protein for building and repairing body cells and tissues.

For fish, go for deep-sea fish that contain high levels of omega-3 fatty acids. Omega-3 fatty acids can maintain brain function and reduce inflammation and oxidation.

As for red wine, it contains high amounts of polyphenols.

Low intake of red meat, sweet foods, and saturated fat.

- Red meat: 4 servings a month.

- Sweet foods: 3 servings a week.

High intake of red meat has been linked to an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease. There are several possibilities that contribute to this. The high haem content in red meat can act as a toxin when this substance is not digested properly. Secondly, the high content of saturated fat in red meat is associated with increased oxidative stress.

RECONCILING THE MEDITERRANEAN DIET WITH OUR MALAYSIAN DIET

Although this diet is practiced by the people in Mediterranean countries that have a different dietary culture from Malaysians, it is possible to include their recommendations into our Malaysian diet.

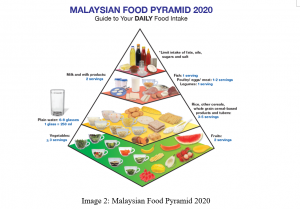

In fact, there is a high similarity between the Mediterranean Diet Pyramid and the Malaysian Food Pyramid.

Image 1 shows the Mediterranean Diet Pyramid while Image 2 shows the latest Malaysian Food Pyramid. Click on these images for larger, clearer versions.

- Both the Mediterranean diet and the Malaysian Food Pyramid encourage the consumption of fruits and vegetables, followed by the consumption of various grain products, especially whole grains.

- In line with the recommendations of the Mediterranean diet, the Malaysian Food Pyramid also recommends the selection of lean meat and the incorporation of plant protein sources such as legumes in a simple daily diet.

- Both of these pyramids also emphasize limiting the intake of fat, oil, sugar, and salt.

However, a slight difference is that the Mediterranean diet emphasizes the consistent use of olive oil.

The Mediterranean diet also encourages moderate wine consumption, but individuals may make decisions on whether to include this into their diet, based on their own personal religion and beliefs.

HOW TO USE THE MALAYSIAN FOOD PYRAMID AS A FOUNDATION TO INCORPORATE MEDITERRANEAN DIET IN OUR LIVES

One simple way is to follow the Malaysian Healthy Plate concept.

The Malaysian Healthy Plate concept. Click on the image for a larger, clearer version.

- The first quarter of the plate is allocated for carbohydrate food sources such as rice, bread, grains, and others.

- The second quarter is allocated for protein sources such as legumes, fish, chicken, and meat.

- The remaining half is allocated for fresh vegetables and fruits.

The “Suku Suku Separuh” (“Quarter Quarter Half”) concept emphasizes portion control and balanced meals. Following it allows us to adhere to the recommendations of the Malaysian Food Pyramid.

Additionally, the cooking methods used in meal preparation also play a key role in enabling the incorporation of the Mediterranean diet into our Malaysian diet. We can use olive oil in the grilling, baking, and roasting of meat, fish, and vegetables. It can also be used as drizzle for our salads and ulams.

References:

- Chu, C., Yu, L., Chen, W., Tian, F., & Zhai, Q. (2021). Dietary patterns affect Parkinson’s disease via the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Trends in food science and technology, 116, 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.07.004

- Bexci, M.S. & Subramani, R. (2018). Decoding Parkinson’s associated health messages in social media pages by Malaysian service administrators. Malaysian journal of medical research (MJMR), 2(4), 64-72.

3. Torti, M., Fossati, C., Casali, M., De Pandis, M. F., Grassini, P., Radicati, F. G., Stirpe, P., Vacca, L., Iavicoli, I., Leso, V., Ceppi, M., Bruzzone, M., Bonassi, S., & Stocchi, F. (2020). Effect of family history, occupation and diet on the risk of Parkinson disease: A case-control study. PLoS one, 15(12), e0243612. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243612 - Molsberry, S., Bjornevik, K., Hughes, K. C., Healy, B., Schwarzschild, M., & Ascherio, A. (2020). Diet pattern and prodromal features of Parkinson disease. Neurology, 95(15), e2095–e2108. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000010523

- Georgiou, A., Demetriou, C. A., Christou, Y. P., Heraclides, A., Leonidou, E., Loukaides, P., Yiasoumi, E., Pantziaris, M., Kleopa, K. A., Papacostas, S. S., Loizidou, M. A., Hadjisavvas, A., & Zamba-Papanicolaou, E. (2019). Genetic and environmental factors contributing to Parkinson’s disease: A case-control study in the Cypriot population. Frontiers in neurology, 10, 1047. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.01047

- Gao, X., Chen, H., Fung, T. T., Logroscino, G., Schwarzschild, M. A., Hu, F. B., & Ascherio, A. (2007). Prospective study of dietary pattern and risk of Parkinson disease. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 86(5), 1486–1494. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1486

- Yin, W., Löf, M., Pedersen, N. L., Sandin, S., & Fang, F. (2021). Mediterranean dietary pattern at middle age and risk of Parkinson’s disease: A Swedish cohort study. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 36(1), 255–260. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.28314

- Alcalay, R. N., Gu, Y., Mejia-Santana, H., Cote, L., Marder, K. S., & Scarmeas, N. (2012). The association between Mediterranean diet adherence and Parkinson’s disease. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 27(6), 771–774. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.24918

- Rusch, C., Beke, M., Tucciarone, L., Dixon, K., Nieves, C., Jr, Mai, V., Stiep, T., Tholanikunnel, T., Ramirez-Zamora, A., Hess, C. W., & Langkamp-Henken, B. (2021). Effect of a Mediterranean diet intervention on gastrointestinal function in Parkinson’s disease (the MEDI-PD study): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ open, 11(9), e053336. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053336

- Rusch, C., Beke, M., Tucciarone, L., Nieves, C., Jr, Ukhanova, M., Tagliamonte, M. S., Mai, V., Suh, J. H., Wang, Y., Chiu, S., Patel, B., Ramirez-Zamora, A., & Langkamp-Henken, B. (2021). Mediterranean diet adherence in people with Parkinson’s disease reduces constipation symptoms and changes fecal microbiota after a 5-week single-arm pilot study. Frontiers in neurology, 12, 794640. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.794640

- Calder P. C. (2006). n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and inflammatory diseases. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 83(6 Suppl), 1505S–1519S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1505S

- The Hellenic Health Foundation. (n.d.). Dietary guidelines for adults in Greece. https://www.hhf-greece.gr/hydria-nhns.gr/adultdietarytext_eng.html

- Bisaglia, M. (2022). Mediterranean diet and Parkinson’s disease. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24010042

- Lange, K. W., Nakamura, Y., Chen, N., Guo, J., Kanaya, S., Lange, K., & Li, S. (2019). Diet and medical foods in Parkinson’s disease. Food science and human wellness, 8(2), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fshw.2019.03.006

- Foo Chung, C., Pazim, K., & Mansur, K. (2020). Ageing population: Policies and programmes for older people in Malaysia. Asian journal of research in education and social sciences, 2(2), 92-96. https://myjms.mohe.gov.my/index.php/ajress/article/view/10227